253 total views

Today the Church commemorates a great Bible scholar of the fourth century, Saint Jerome. He made a big contribution by daring to translate the Sacred Scriptures in a language people could understand. By his time, less and less people could understand Hebrew and Greek anymore. Latin was fast becoming the more commonly spoken language. Jerome saw the need to come up with a translation of the Hebrew and Greek books of the Bible into the kind of Latin that was spoken, not by the scholars, but by the Vulgus (nowadays we would say the “masa” or the common people). That is why we have the so-called Latin translation of the Bible known as the Vulgata (the Latin equivalent of the English “vulgarized”.)

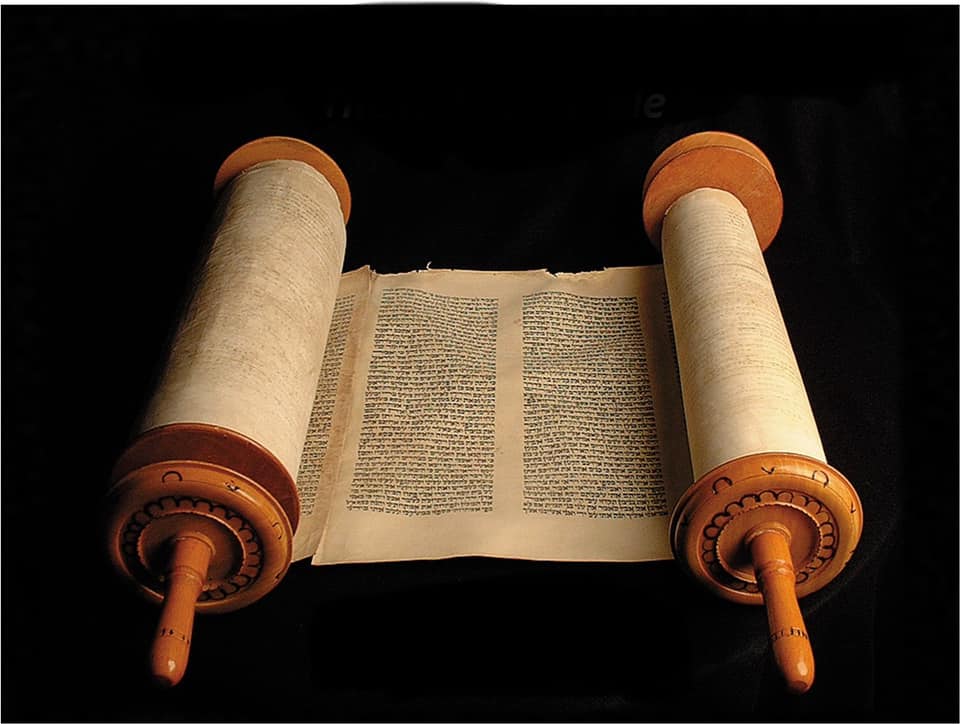

You probably have noticed already that in my homilies, I rarely say “The Bible says this or that…”. We don’t usually talk that way as Catholic Christians. That is more common among other Christian denominations. Why, you might ask? Well, because “Bible”, literally means a whole library! For us Catholics, it’s a collection of 73 books, 46 from the Old Testament, and 27 from the New Testament. So when people say, “The Bible says this or that,” I ask, “Where in the Bible? In which book?” They were not written all at the same time. They were composed through a span of more than 1000 years, both Old and New Testaments. Some are older, others are younger.

It took a long time before they were put together into one collection. And up until now, Christians have yet to agree exactly which books are supposed to be part of the collection and regarded as Sacred writings. That does not mean they just dropped from heaven. They were written by ordinary human beings like you and me but they have been recognized as inspired by the Holy Spirit. In short, as God’s Word in human words.

Our first reading today from Nehemiah gives us an idea how they did a public reading of sacred writings in ancient times. Remember, they had no sound system yet. If Ezra was reading from an elevated podium before an audience of one thousand people, how would you expect those in the middle and those at the back to hear and understand what was being read? The writer tells us Ezra had assistants called the Levites who took care of that. The congregation was grouped into smaller groups with one Levite assigned to each. Their work was to echo or repeat to the smaller groups what Ezra was reading and explaining from the podium.

I get the impression that Jesus is adopting the same method in the Gospel. Luke tells us he appointed seventy two other coworkers aside from the twelve apostles in his core group. I think their role was similar to what the Levites did in our first reading—to echo the Rabbi’s preaching.

But it looks like Jesus was not contented with that. He sent them two by two in order to follow up on those who had listened to Jesus in the larger assembly, but this time in their homes. That should be the reason why he calls it a “harvest”. It presupposes that something had been previously planted already.

In the first reading, we hear that the people in the assembly were moved to tears by Ezra when he read and interpreted the book of the law of Moses to them. Take note how long—for six hours! “From daybreak until midday!” Wow. And they remained attentive and interactive. Listen to how Nehemiah describes them, “All the people were weeping as they heard the words of the law” being read and explained to them.

At some point he calls for a lunch break and tells them, “Stop crying, for today is holy to the Lord.” It means it was Sabbath. Then he said, “Do not be saddened this day, FOR REJOICING IN THE LORD MUST BE YOUR STRENGTH.” The people therefore “went to eat and drink…and to celebrate with great joy, for they understood the words that had been expounded to them.”

I am sure you also get to experience this once in a while. Sometimes, after Mass, some people greet the parish priest and say, “Father, you know, it’s like every word that you said was meant for me.” Of course that is not always the case. There are also instances when we feel like miserable failures. Like when someone comes and says, “Wow, Father, that homily was bulls eye for many people I know in the parish.” You keep quiet and wish you could tell him, “I didn’t mean it for them. I meant it for you.”

I was reading a reflection written by Saint Jerome 1600 years ago in the office of the readings this morning. He said we get to know the power and wisdom of God through the Scriptures, and that, since Christ himself is the power and the wisdom of God, “Ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ.” Like Christ whom we proclaim as truly divine and truly human, so also the Scriptures.

At each Mass, we are being fed from two tables—the table of the Word, and the table of the Eucharist, at which we received the Word made flesh in Christ, who offers his body and blood as food. St. Augustine it a different kind of food—we don’t change it; it changes us. We don’t receive Christ and make him a part of our bodies. No. When we receive Christ, he transforms us and make us part of his body, his redeeming life and mission.