406 total views

One of the most beautiful and well remembered stories found only in the gospel of Luke is about the Good Samaritan (10:29-37). Here, Jesus is tested by a lawyer, an expert in the Jewish law, probably a scribe (v25). In the ensuing process of question and counter-question it is the lawyer himself (v27) and not Jesus (Mt 12:28f) who gives the summary of the law in quoting the combined Pentateuchal texts (Dt 6:5; Lev 19:18), the synthesis of the law and the prophets which is upheld by Jesus and eventually embedded in the life of the early Church (v28; Mt 22:37f; Rom 13:9; Gal 5:14; Jas 2:18). The joined love of God and neighbor lies at the heart of the Christian ethic.

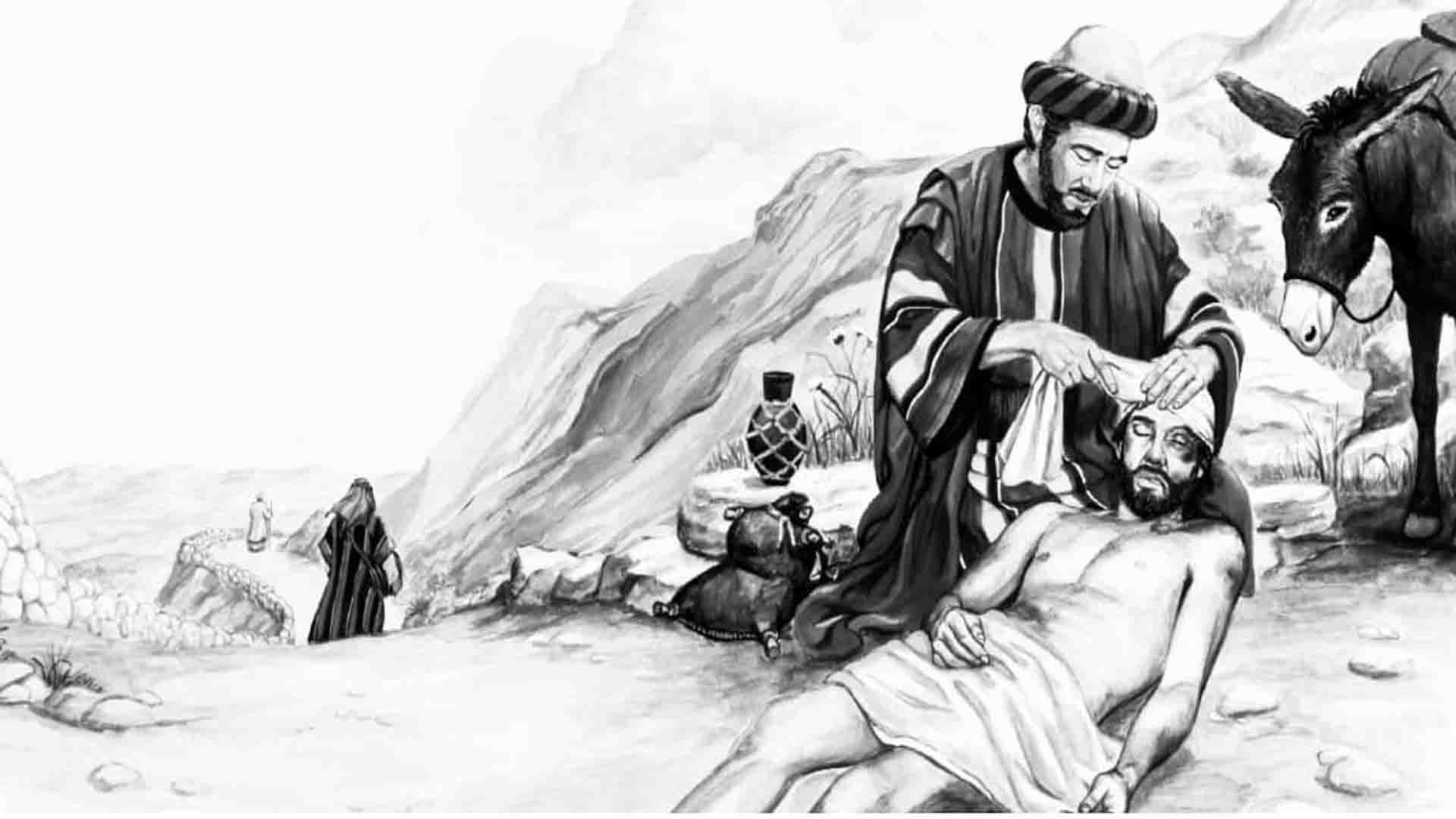

The term “πλησίον” (plēsion) is commonly translated in the Bible as neighbor, in the sense of one who lives adjacent or nearby, or surrounding region, as well as friend or companion. It can even refer generally to one’s fellow human being. But coming from the mouth of an expert on the law (who wish to ‘vindicate himself’ v29), the unexpected response of Jesus shattered his limited idea about neighbor, that is, restricted only to one’s fellow Israelite (Ex 20:16,17, 22:7f; Lev 19:23f; Dt 5:20, 15:2, 24:10; Is 41:6). Because in the story Jesus makes the central figure a Samaritan, a religious and social outcast, ritually unclean in Jewish eyes (John 4:9), who provides for a dying Jew who was bypassed by cultic personnel, a priest and Levite, to avoid becoming ritually unclean (Lev 21:11)

The rich narrative shows the basic story’s contrast: the pity and kindness shown by a schismatic Samaritan to an unfortunate mistreated human victim stands out vividly against the heartless, perhaps law-inspired indifference of two representatives of the official Jewish cult, who otherwise are expected by their roles to deal properly with the afflicted persons. It is true that the story implies that a ‘neighbor’ is anyone in need with whom one comes into contact and to whom one can show pity and kindness even beyond the bounds of one’s own ethnic or religious group. But there is more.

In the context of the final question of Jesus, it centers around the one who acted as neighbor (v36), none other than the Samaritan, the person who himself shown benevolence or ‘neighborliness’ to others. It is no longer whether the victim of the highway robbery could be considered legally a neighbor to either the priest, the levite or the Samaritan, but rather which one of them acted as a neighbor to the unfortunate victim.

The fact that the lawyer cannot bring himself to speak the word “Samaritan” but only “the one who… (v.37) shows his reluctance to accept Jesus’ teaching: “that love of neighbor embraces a Jew, a Samaritan or anyone else.

The parable’s importance for us Christians lies in its upholding the priority of the spirit over the law. It highlights openness to, and the need to care for, all people without discrimination. The story is a reminder to emulate God by showing mercy and compassion, for real love of God and neighbor is intimately connected to action: “go and do likewise” (v37); and we will “inherit eternal life” (vv25,28).